| |

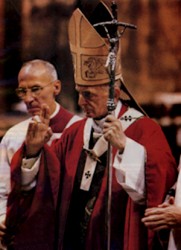

Paul VI

On the Centenary of his Birth |

"Our name

is Peter"

A leading Italian Vatican commentator

looks back over the life of Giovanni Battista Montini,

his cultural origins and his relationship with

Angelo Roncalli, John XXIII. The Paul VI Pontificate

marked by two-way fidelity - to Tradition and to

the appeals of the modern worldby Giancarlo Zizola |

|

The

scientific initiatives undertaken by the Paul VI Institute in Brescia and parallel

historical research delving deeper than ever before into the archives have helped us take

a more fitting and closer look at the complexity of the figure of Paul VI. Now, the

centenary of his birth - on September 26, 1897 in Concesio (Brescia, North Italy) - is an

opportunity to look back with a fresh eye and recapitulate, it is hoped, without the

baggage of emotion-charged controversy.

Montini was raised from a very young age on

Catholicism reconciled with democracy. He became an assistant of the Italian Catholic

Universities Federation (FUCI) at the time of conflict with Fascism. He translated

Maritain and he served as a bridge in the Vatican Secretariat of State between the Pope

and the more dynamic elements of Europe's Catholic intelligentsia. But that was until Pius

XII gave in to pressure from the so-called "Roman Lobby" and was obliged to

exile him to Milan as archbishop

|

|

One criterion to emerge from the Montinian historiography and which has taken

root is that of democratic Catholicism, symmetrical to that other summary description of

prudent reformism where prudence, to put it in Cardinal Giuseppe Siri's words,

"advises courage, temerity only excluded". Son of a journalist who became a

Popular Party (forerunner of Christian Democracy) member of parliament under the Party

founder, Father Sturzo, Giovanni Battista Montini was raised from a very young age on

Catholicism reconciled with democracy. With this orientation, he became an assistant of

the Italian Catholic Universities Federation (FUCI) at the time of its conflict with

Fascism. He translated Les trois rÚformateurs (The Three Reformers) by Jacques Maritain

and he served as a bridge in the Vatican Secretariat of State (as Substitute Secretary)

between the Pope (Pius XII) and the more dynamic elements of Europe's Catholic

intelligentsia. But that was until Pius gave in to pressure from the so-called "Roman

Lobby" and was obliged to exile Montini to Milan as archbishop. Documents which are

now familiar prove beyond any reasonable doubt that Pope Pius XII's decision to deprive

himself of his Substitute Secretary of State was in direct connection with the Roman

Lobby's offensive launched in early 1954. In a note, Father Riccardo Lombardi writes of

this group's intentions to "remove Montini's influence in Italian politics and give

it to Tardini (Fanfani [future Christian Democrat prime minister] is Montini's point of

reference)". |

And this is sufficient proof that a politico-ecclesial operation had been mounted to

close any door left open to the political left even at the cost of the autonomy of

Catholic militants in the Christian Democratic Party (cf Giancarlo Zizola, Il microfono di

Dio, Pio XII, padre Lombardi e i cattolici italiani, Milano 1990 (God's Microphone, Pius

XII, Father Lombardi and Italian Catholics), pages 348 ff). For, this (open door) was

considered to be ceding on principle to the Marxist forces in the Italian Government. In

this context, Montini's removal from the Secretariat of State, which was made public on

November 3 1954, represented the apogee of an overall re-shuffle. In the spring, it forced

the resignation of GIAC (Italian Youth group of Azione Cattolica) chairman Mario Rossi and

Vittorino Veronese's replacement as president general of Italy's Azione cattolica two

years before - year of the "Operazione Sturzo" (Catholic and right-wing alliance

for local elections in Rome) - with Luigi Gedda.

Abundant material has emerged from research on Montini's reforming mind-set,

but what he himself confided to Father Lombardi in 1950 is a valid indication on its own.

He was discussing the need for radical spiritual reform of the Papacy and he said:

"Once deprived of temporal power, the Popes retained only the exterior forms, the

only aspect they were able to conserve. When Reconciliation came (Church-State Concordat),

those forms remained. But they have to go, and one day a Pope will hang up that mantel ...

The pope should leave the Vatican and all of them there with their salaries and go, at

least at certain times, to Saint John Lateran to live with his seminarians, with his

people, under a different, new ceremonial ... He should only go back to the Vatican now

and then. And at Saint John's the new governance of the Church should begin, as it was

with poor Peter ... " (ibidem, page 232).

It was

no accident that, together with Giacomo Lercaro, Montini was the only Italian bishop to

propose a reform program to the Council that was not mediocre. |

|

This is certified by the ante-preparatory Acts of Vatican II and the first volume of

Storia del Concilio Vaticano II (The History of the Second Vatican Council) on the

genesis, both at the time and in the more distant past, of the assises convened by John

XXIII (cf Various Authors, Storia del Concilio Vaticano II, I, Peeters, Leuven, SocietÓ

editrice Il Mulino, Bologna 1995, The History of the Second Vatican Council).

Moreover,

John XXIII's special bond with Monsignor Montini while he, John, was still patriarch of

Venice and even before that, cannot be explained by personal friendship, however rich and

significant. Still to be analyzed are the topics of discussion that Roncalli and Montini,

newly appointed archbishop of Milan, addressed in talks on August 15, 1955 at the former's

family home in Sotto il Monte, Bergamo (North Italy). The marble slab on the wall at the

house, CÓ Martino, commemorating the meeting tells us that they "engaged in

prevident talks about the Church's destiny". There had been a mysterious meeting of

the minds of the two popes of the future. When elected, John XXIII rapidly proved able to

invent ways to re-integrate the exile fully within the symbolical circle of the supreme

government. He made him first among his cardinals and gave him decisive roles to play in

the Council's management and review.

|

Thus the archbishop of Milan found himself with a legacy which many would

have liked to have seen dismantled as soon as possible. But it was a legacy for which

Montini had battled and it consisted in taking action so that the Church would be able to

address all men, beyond the walls and all the barriers; this, without mixing up the Gospel

cause with that of coalition of free peoples, without seeking a remedy outside of the

Church in political alliances but in the deepest depth of its tradition, in its own reform

and rejuvenation; beating down the fences separating Christ's various sheepfolds and

seeking to serve "men as men, and not just as Catholics, to defend everywhere and

above all the rights of the human person, and not just those of the Catholic Church",

according to Pope John's testament.

So,

because of those old bonds of solidarity, it was up to Montini to provide a strategic

framework and to bring minds gradually around to John's brusque about-turn without running

any risk of rift. From this came the Pontificate's principal lines of action whose

adoption was encouraged by the 1963 conclave though within margins already being drawn by

tension that would be the mark of things to come: the Council's resumption within a papal

context (but in the absence of revolutionary excesses which Montini had already criticized

in his introduction to The Three Reformers); prudent reform of the ecclesiastical

institutions starting with the Roman Curia; development of ecumenical dialogue; the search

for new relationships between the Church and modern society by every useful means to

preserve and consolidate Christian society itself, beset as it was by secularization. |

The

"programming" encyclical Ecclesiam suam in 1964 pictured the Church's mission as

three circles of dialogue within its own community - ecumenical with the sister Churches,

pastoral and cultural with the modern world.

In his

program, the Pope incorporated the legacy of John's "springtime" within the

institutional framework as well as Vatican II orientations though they were still not in

force. Father Giacomo Martina (Jesuit Church historian) clarified the point well in his

book: "Montini would probably not have opened the Council but at the time he appeared

to be the best man to bring it to a close ... He was considered the more authoritative

expression of John XXIII's thinking and, at the same time, the man who, boldly but with

more order and method, was capable of realizing the ideals of the Pope who had just

died" (cf G. Martina, Storia della Chiesa, da Lutero ai nostri giorni, IV L'etÓ

contemporanea, Brescia 1995, page 318, History of the Church, from Luther to the Present

Day).

Paul VI's contribution to the Council has been appraised in different ways. The

priority he gave to the juridical-institutional dimension - necessary in any event to

commit people to the Conciliar innovations - was contested on the grounds that it would

mean unduly sacrificing the kerigmatic and prophetic dimension. In the Council

proceedings, he highlighted the Papacy's function of primacy, monitoring discussions and

intervening himself several times; this, so that he himself could address the crucial

themes (priestly celibacy, birth control, Curia reform) and so that he could arbitrate

between the majority and the minority. This he did by modifying the scope of a few

contexts in a bid to absorb dissent and to foster the maximum ultimate consensus.

With

his motu proprio Integrae servandae in December 1965 on the eve of the closure of the

Council, he proceeded to reform the Holy Office which, five years later, was endowed with

a ratio agendi more respectful of an offender's right of defence. |

Paul VI's contribution to the Council has

been appraised in different ways. He highlighted the Papacy's function of primacy within

Council proceedings, monitoring discussions and intervening himself several times; this,

so that he himself could address the crucial themes and so that he could arbitrate between

the majority and the minority

|

|

His efforts to reform the central apparatus were driven by his conviction, expressed in

a discourse on July 14 1965, that "the notion of Church authority has to be analyzed,

to purify it of forms not essential to it (even if in certain circumstances they were

legitimate, such as temporal power) and to bring it back to its original, Christian

criterion". Hence, the creation of a series of new organs, such as the Consilium de

laicis, the Iustitia et Pax Commission and the Secretariats for non-Christians and

non-Believers flanked by the Secretariat for the Union of Christians. Through this organ,

Pope John had removed some of the Holy Office's monopoly in 1960 setting ecumenism at the

heart of the Roman Church's central government. Between 1965 and 1968, the Vatican under

Paul VI appeared to be a frenzy of reform, sustained by intensive instruction by the Pope

in person so that the Council would be assimilated by the whole "people of God",

independently of a hostile nucleus of strong resistance in the Roman Curia. On August 15

1967, a general reform of the Curia, decreed by the constitution Regimini Ecclesiae

Universae, introduced major structural changes (rejection of the concept of

"career", the imposition of age limits and shorter-term mandates, a ban on

"role accumulation", the removal of the top-ranking mandates on the death of the

pope, a new managerial role for the Secretariat of State over other offices and, above

all, the recuperation of a more spiritual and pastoral vision of service).

The introduction of age limits obliged some powerful figures of the old

Curia, such as Tisserant, Ottaviani and Pizzardo, to retire from the scene. For the first

time, responsibility for central offices was entrusted to pastors from the national

Churches in the various continents. Paul VI's own Secretary of State, former secretary of

the French Episcopate Jean Villot appointed on the death of Cardinal Amleto Cicognani, did

not come from diplomatic ranks. Supervision of the whole apparatus was assigned to

Giovanni Benelli, a young prelate whom the Pope would later be obliged to do without in

1977. He sent him to Florence as cardinal archbishop under pressure from the Curia which

was disgruntled at Benelli's intrusive approach.

Piece

by piece, the sacramental and regal form of the Papacy disappeared. |

|

The renunciation of the tiara on the Council's altar introduced exterior modernization.

The noble Papal guard was discharged, the Pontifical court simplified and the Pontifical

army corps disbanded. Vatican diplomacy itself was reformed. It was confirmed as a

structure but brought back - in typical Montinian style - to the realm of ecclesial

functions, in service to the communion between the Papacy and the local Churches. Even the

powers of the cardinalate were reduced with the motu proprio Ingravescentem aetatem

(November 21, 1970) depriving cardinals over 80 of a vote in a Papal election. With the

constitution Romano pontifici eligendo (October 1, 1975), Montini established that the

electoral body of the College of Cardinals would have 120 members. The

internationalization of the College of Cardinals under Paul VI was so sweeping as to

reduce the traditional hegemony of the Italians and Europeans generally in conclave. At

the end of his Pontificate, there were as many non-European voting cardinals as European,

with 12 Africans, nine Asians, 21 Latin Americans, three from the Pacific area and ten

North Americans. In the College of Cardinals moulded by Paul VI, the number of Curia

cardinals with a vote fell to an all-time low with a record high of cardinal bishops in

residence on their home ground in 30 different countries.

|

Thus, the institutional stage was set for the election of a non-Italian

pope.

In the

general post-Conciliar drifting, especially in the wake of circumstances in 1968

(anti-establishment street demonstrations in Europe), the Montinian quest for reform

seemed to be crudely put to the test by the caliber of more incisive requests coming in.

Cases in point were the demands of the Dutch Church. Anti-institutionalism was compounded

by a general ecclesial crisis within the Church. Many priests and religious shirked their

vocations, lay association-forming went into serious decline and the Church was becoming

increasingly polarized. According to Antonio Acerbi (Church historian), who split the

Pontificate into different periods with events in 1968 serving as a dividing line,

"the frenzied development of innovations without the filter of due reflection, the

crash of collision between irreconcilable attitudes, the impassioned thrust of collective

causes, a sign of the times, offended the Pope's sensibilities. Pyschologically, he was

extraneous to the new social ferments, to the cultural climate of the hour and to the

tension inside the Church. Reflective, circumspect, sensitive to the light and shade of

thought, cautious in decision-making, the Pope was a man who envisioned dialogue unfolding

in an atmosphere of serene nobility of the mind, sustained by an encounter principally of

the spiritual kind. This is why his words often had the tone of an appeal, of a man

disillusioned and anxious" (A. Acerbi, "Il pontificato di Paolo VI", in

Storia dei Papi, edited by Martin Greschat and Elio Guerriero, Cinisello Balsamo 1994,

page 935, The Pontificate of Paul VI, in History of the Popes).

"

'The Doubtful Pope' he certainly was when faced with contestation that even struck out at

some irrenouncable convictions of his own, such as the safeguarding at all costs of total

monarchical power, as it had been before him and as he felt he had to ensure it would

continue, at the disposition of his successors, after him" (J. Grootaers). |

But

that he was profoundly persuaded of this did not mean he had no awareness of the

complexity of the new problems facing the Church in the new age of personal rights and

democratization. In a personal note at some point in 1975, he makes an attempt at

self-definition: "My state of mind? Hamlet? Don Quixote? Left-wing? Right-wing? ... I

don't see myself in any of them" (cf Pasquale Macchi, "Discorso di

commemorazione", Notiziario dell'Istituto Paolo VI, 1, page 50, Commemoration

Address, Bulletin of the Paul VI Institute). Perhaps in his ponderous deliberations, he

was suggesting a model of magisterium which would certainly not find its niche in defining

and reproducing the traditional certainties with the presumption of unifying and deducing

the unprecedented complexities of modern society and of the Church itself. In this, his

naturally hesitant psyche was more likely to have been the reflection of the problematical

nature of the modern culture whose child he also was even as he was a son of dogma. This

created positive tension in him, between his being Peter and his being Paul, between his

calling to conserve the past and his other vocation to seek the new that would be destined

to become the tradition of the future.

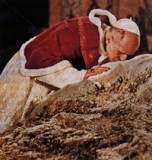

And yet, the Pope of dialogue manifested

his conviction that the dogmatic prerogatives of the Church's Petrine function had to be

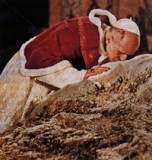

fenced off, untouched. The Peter kneeling at the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem or prostrate,

kissing the feet of the Metropolitan Melitone, were one and the same as the Peter who did

not hesitate to say during his visit to the World Council of Churches in Geneva in 1969:

"Our name is Peter"

|

|

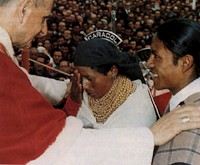

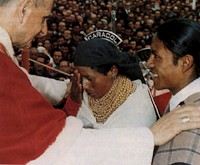

And yet, the Pope of dialogue manifested his conviction that the dogmatic

prerogatives of the Church's Petrine function had to be fenced off. The Peter kneeling at

the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem or on the shores of Lake Tiberias during his first great

visit to the Holy Land in 1964, the Peter prostrate, kissing the feet of the Metropolitan

Melitone sent by the Patriarch Athenagoras to the 1975 Vatican celebrations for the tenth

anniversary of the abolition of reciprocal excommunication by Rome and Constantinople -

they were one and the same as the Peter who did not hesitate to say during his visit to

the World Council of Churches in Geneva in 1969: "Our name is Peter". The debate

in 1970 generated by Hans KŘng's book, Infallible? A Question, resulted in a severe

re-assertion by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith of the 1870 doctrine on

Primacy. Montini was up front vindicating "the full, supreme and universal authority

of the Roman Pontiff, authority which cannot be reduced to particular circumstances"

(Discourse to the secretariat of the Synod of Bishops, October 14 1974).

He

showed the same unequivocal concern for collegiate reform of the Pontifical government. |

Already during the Council, the Papal reservations manifest in his Nota praevia

designed to counter-balance the collegiate orientations put to the Assembly's vote, were

an illustration of the Pope's desire to reduce the collegiate factor to a mystical

dimension "of the affections", that is, a subaltern form of assistance to a

pontifical monarchy intolerant for the moment of any restrictions. On September 15, 1965

while the Council continued, the institution of the Synod of Bishops itself was limited by

its "direct and immediate" subjection to pontifical authority and by its normal

function as a mere consultative body. This same notion that pontifical authority could not

be derogated accompanied Paul VI's ecumenical policy, though this did not make him

unreceptive to the "sister Churches" formula in relation to the Orthodox East.

Moreover in 1976, he allowed the Anglican-Catholic Joint Commission to issue a Declaration

on Authority in the Church reformulating in patristic terms the conditions under which

Canterbury would accept Papal primacy. But the key to the primacy's collegiate

restructuring seemed to be so foreclosed that the Cardinal Primate of Belgium Suenens felt

motivated to take issue.

In a 1969 interview that made headlines, he observed that this version of

the Synod was "a caricature of the collegiate factor". With this daring

criticism, he had highlighted the detachment of the progressive bloc, protagonist of

Council reforms.

However,

this (progressive) alliance had already shown signs of weakness in the crisis that

followed the publication of the encyclical Humanae vitae in 1968. Two years later saw the

conservatives engage in virulent anti-papal contestation, their interpreter being the

fundamentalist Marcel Lefebvre. Unable to countenance any compromise of the Council's

authority or of total acceptance, Council that Lefebvre continued to describe as

"schismatic", the Pope decided to declare the rebel bishop of Ec˘ne suspended a

divinis in July 1976, knowing full well that Lefebvre's puppeteers were to be found inside

the Roman Curia.

It was

a paradoxical epilogue to Montini's whole compromise strategy by which he sought to

contain the post-Conciliar explosions within a fold that was Roman at long last. |

|

It was during the Holy Year of Reconciliation, proclaimed in 1975, that he made his

ultimate attempt to re-launch the spirit of the Council and so regain control of the

ragged anti-Conciliar trends that Rome only just managed to govern. Even then there were

perceptible cracks in the wall of solidarity built by the reforming currents which had

"made" the Council, currents which then split into a moderate wing and a radical

one. The reform theory founded on institutional compromise proved just as vulnerable in a

Catholic culture. For, all it seemed to be able to do was sublimate the form of the

societas christiana, unchaining it from anti-modernism and from the illiberal residues of

theocratic supremacy over modern society. Not by chance was it the theorist of the

democratic adaptation of the "Christian society" himself, Jacques Maritain, who

would summarize the widespread post-Conciliar disquiet that the crisis in the Church was

precipitating on the front of dialogue with modernity. Vatican II had made one of its most

significant inventive efforts in this sphere, addressed by Maritain in his Paysan de la

Garonne.

There

is no doubt that Paul VI's Pontificate developed and even thrusted in that very political

- and theoretical - direction. In his speech to the United Nations in New York on October

4, 1965 he presented himself to the world as the spokesman, not of any religious power but

of a Church which was an "expert in humanity" with a bi-millennial patrimony of

ethics to offer in the cause of world peace, justice and security.

|

On his visit to Bombay in 1964, he placed the accent on service to

underdeveloped peoples. His proposal that governments devolve a minimum of their military

spending in their favor went unheeded. In the years to come, the Pope would travel to

Bogota, Kampala and Manila, stopping off in Hong Kong in 1970 where he invited Mao Tse

Tung's China to engage in dialogue.

On the

international scene, Paul VI significantly revised and developed the policy of

"active neutrality" proposed by John XXIII. The Pontifical position, critical of

America's persistence with the Viet Nam War, was outlined without reticence by the Pope in

dramatic audiences with Presidents Johnson and Nixon. Diplomatic initiatives and public

opinion campaigns to stop the war, and keep the Catholic Church out of the fray of

dominant strategic interests in South East Asia, had no immediate effect. It was not known

until after the event that the Pope had tried to stop the American bombing of Chinese

nuclear plants in 1965. |

However, despite the Church's political powerlessness in the West, it was playing the

role of critic, a part assumed to preserve the Church's universal nature in its service to

all men and all peoples and, primarily, to the victims of injustice.

Montini,

the "political" Pope nurtured undoubted faith in the instruments of pure reason.

In his efforts for peace in Viet Nam there is no doubt about his preference for diplomatic

options over prophecy, as Cardinal Lercaro once apostrophized in his regard. With

Ostpolitik, interpreted by then Monsignor Agostino Casaroli (future Cardinal Secretary of

State), Paul VI did succeed in extricating a series of modus vivendi from the Communist

regimes of central-eastern Europe. Apart from the relative immediate advantages, the

arrangements at least included official Communist recognition of the right of religions to

public statutes. Despite opposition from some Catholic sectors, fearful that any real

rapprochement would mean yielding on ideology, the Pope pressed on without hesitation with

his policy of dialogue. He obliged Cardinal Mindszenty to come out of voluntary exile and

leave the confines of the American Embassy in Budapest, Hungary, where he had taken refuge

during the anti-Soviet revolt in 1956. The Pope offered him hospitality in Rome. At the

same time he agreed to "exile" Monsignor Beran in Rome, safe from Communist

house arrest in Czechoslovakia but then sacrificed him, now a cardinal, on the altar of an

understanding with Prague designed to normalize Church life in the republic.

In general, he sustained the approach of

"courageous transformations, urgent reforms" as a solution for the problems of

global underdevelopment. And he vindicated the principle that "the surpluses of rich

countries must serve the poor countries"; this, also to prevent that "the wrath

of the poor fall upon the avarice of the rich"

|

|

Paul VI's Ostpolitik no doubt reached its apex with the admission of the Holy

See as a full member of the Conference for Security and Cooperation in Europe. The Final

Act of the Helsinki process, incorporating the Holy See's requests to guarantee the right

to freedom of conscience, religion and worship in Member States - therefore including the

Soviet Union and Europe's Communist countries - was signed on the Pope's behalf by

Casaroli on August 1, 1975. This was not just the positive outcome of a policy which was

ably conducted so as to be impervious to any kind of connotations of "crusade"

or confrontation; it also marked the start of a longer-term dynamic that would slip

elements of comparison and contradiction and questions of rights into the closed

ideological systems of the Soviet kind, elements that could explode in the medium-long

term. This perspective drawn by Paul VI, though not without internal difficulties and

initial justified uncertainty, would be brought to fruition by John Paul II ten years

later. |

After

manifesting his adherence in 1971 to the Nuclear Arms non-Proliferation Treaty Pope Paul

VI, in the 1977 paper, The Holy See and Disarmament, suggested that the United Nations

adopt a "disarmament strategy" that would include access to international

financing for countries reducing their military budgets in favor of social spending. It

was not just commitment to world peace that found in Paul VI a convinced supporter but

also the Church's whole social doctrine. And this was in contrast to the hypotheses about

(Church) withdrawal from the scene being aired by radical theologians. In his encyclical

Populorum progressio (March 26, 1967), he reiterated the biblical principle of the

universal destination of goods and he thus distanced himself from any kind of liberal and

individualistic interpretation of private property. Revolutionary insurrection as a means

to an end curried no favor with the Pope, who believed this to be the road to "new

injustices, new imbalances". But, in keeping with Saint Thomas, he did concede that

"evident and prolonged" tyranny presented an exception. In general, he sustained

the approach of "courageous transformations, urgent reforms" as a solution for

the problems of global underdevelopment. And he vindicated the principle that "the

surpluses of rich countries must serve the poor countries"; this, also to prevent

that "the wrath of the poor fall upon the avarice of the rich". One significant

practical example of Pontifical prudence in relation to revolutionary methods can be seen

in the Holy See's "wait and see" policy towards the liberation movements in

Portuguese colonies in Africa.

The Papal audience of July 1, 1970 with the leaders of these movements was

played down in the interests of relations with Portugal even though Montini's wariness of

that country's then regime under Salazar was no secret. Nor was his desire to be free of

the onus of this regime's long-standing civil protectorate of the Church and, in

particular, of the appointment of bishops.

In the

last years of his Pontificate, Montini had such a clear perception of the dilemma

presented by the theory of a Christian society, so dear to him, that he felt he had to

shift the paradigm. The encyclical Octogesima adveniens (May 14, 1971) recognized that the

Church's traditional theoretical apparatus had lost its historical and practical relevance

in the socio-political field. It went so far as to renounce any claim to provide the

ultimate, omnivalent answers to social problems. Far-ranging repercussions were to follow

this admission: "Given so many different situations, it is hard for Us to pronounce

any one word, as a solution proposal with universal value. This is not Our ambition or Our

mission. |

|

It is the task of the Christian communities objectively to analyze the situation in

their own countries, to see clearly in the light of the unchangeable words of the Gospel,

to draw upon principles of reflection, norms of judgement and directives for action in

keeping with the Church's social teaching which has developed in the course of history ...

In the last years of his Pontificate,

Montini perceived the dilemma of the Christian society theory, so dear to him, with enough

clear-sightedness that he felt he had to shift the paradigm. The encyclical Octogesima

adveniens of 1971 recognized that the Church's traditional theoretical apparatus had lost

its historical and practical relevance in the socio-political field. It went so far as to

declare renunciation of any claim to provide the ultimate, omnivalent answers to social

problems

|

|

With the help of the Holy Spirit, in communion with the bishops in charge

and in dialogue with their Christian brethren and with all men of goodwill, it is the task

of these Christian communities to discern the options and the commitments that should be

assumed in order to bring about the social, political and economic transformations which

are proving urgently necessary in many cases". This encyclical also went beyond all

the basic formulas of political action by Christians, stressing the need "to

recognize that there is a legitimate variety of possible options" and that "the

same Christian faith can produce different commitments".

These

theoretical enunciations were on a parallel with a secularizaton process which turned out

to be more rapid and more devastating than expected, a process that, day by day, shattered

any prospect of a "Christian society". To the surprise of Catholics who were not

very tuned in to history's unfolding (G. Martina), the referendum for the abrogation of

the divorce law in Italy on May 12, 1974 found that 59.1 per cent of Italians wanted the

law to stay and 40.9 per cent did not. As the result of the abortion referendum in 1981

would confirm, Christianity in Italy was in decline although the hierarchy, with Papal

encouragement, battled on with repeated appeals to the classic Christian sense. |

Paul VI's personal commitment to these efforts to hold back the tide took the form of

interventions directed at ACLI (Christian association of Italian workers), which had

decided to adopt the "Socialist option", and at Catholic candidates running for

election on the Italian Communist Party ticket. While these attempts reflect the Pope's

concern about the workability of the Church's traditional means of guaranteeing its

presence in society, they suggest the overall perception of all the accords, concordats

and other expedients under Paul VI's Pontificate: they can easily be said to have

indicated that the Holy See was officially acknowedging the death of Christendom in all

its ambivalent aspects; this, by agreeing to renounce its privileges of old, the cardinal

principle of religious freedom, the exhaustion of the "Catholic religion as the

religion of State", even in Catholic countries like Spain, Portugal and Italy.

|

The apostolic exhortation Evangelii nuntiandi, fruit of the 1974 Synod, was the

outcome of a search for forms of Christendom at the core of the crisis itself. In the

document, the Pope drafted an image of the Church liberated from the obligations and binds

of political power and committed to the harmless annunciation of the Gospel to all the

peoples, its extreme and only task "on the threshold of a new century, on the

threshold also of Christianity's third millennium". Just as, on his visit to Uganda,

he had prophesied the development of an "authentically African" Christianity, he

was predicting towards the end of his Pontificate the emergence of a plurality of

Christian forms, sprouting here and there from the western form, now played out as a

universal one.

Up to

the end, Paul VI had come up against the difficulties that influential strata of the

ecclesiastical system had had in following him down this road. Even the means and language

of diplomacy were as dust in his hands when in his April 21, 1978 Letter to the Red

Brigades (left-wing Italian terrorists) he appealed for the "unconditional"

release of Aldo Moro, the Christian Democrat Party chairman they had kidnapped (Moro was

later found murdered).

An

analysis of this Pontificate seems to confirm the conclusion drawn by the historian Roger

Aubert who said: "If Paul VI failed in the full realization of the ideal he had set

himself, of two-fold fidelity to Tradition and to the appeals of the modern world ... |

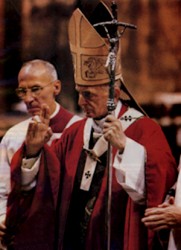

he profoundly transformed the Church nevertheless". When he died, on August 6

1978, the only thing that was on his coffin during the funeral in Saint Peter's Square was

the Gospel, open. It was a supreme religious power's remarkable public demonstration of

simplicity, surrounded in this exterior poverty by the representatives of nearly every

country in the world who had come to bury him. Perhaps it was also the last message from a

Pope whose desire had been to renew the image of the Papacy.