I feel one is duty-bound to mark the date, April 18 1948, with

the full commemoration due to it and I am glad that this can be done without holding back

with the same caution (which would be totally out of order here) that led people to

minimize the event for years or forget it had happened at all so as not to offend one of

the parties defeated in that day's decisive electoral test.

But

after half a century it is no longer a current affair but history. And events have been

such as to remove any further doubt in judging those elections for Italy's first

legislature as a Republic.

I don't

think there is any further liking or regret for the regimes of Stalinist discipline. There

is no doubt about the Soviet Union's determinant role in delivering us of Nazism. What had

to be waived - something other countries failed to do - was any ulterior extension of the

dictatorship from Moscow model. What had happened so recently (before the Italian

elections) in Czechoslovakia (March 1948) had visibly scared even sections of the

population with underlying leftist orientations.

I feel one is duty-bound to mark

the date, April 18 1948, with the full commemoration due to it and I am glad that this can

be done without holding back with the same caution (which would be totally out of order

here) that led people to minimize the event for years

|

There

is one point that should be cleared up right away. Many veterans of the Popular Front

(Communist-Socialist alliance) claim that if they had won there would have been none of

the involutionary trends that so devastated democratic orders elsewhere. Rejection of this

theory definitely does not mean cataloguing Italian Communists and Socialists as

supporters of the Red dictatorship. This could not even have been said of their

counterparts in Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and so on. It is a gratuitous insult to

them to sustain that the opposite is true in order to wash one's hands of them. What is

more, perhaps the various Nennis themselves and Togliattis (Nenni, Socialist; Togliatti,

Communist) would have been called to order and despatched to the sidelines in the event of

indecision. It is neither provocative nor imaginative to say (if anything, it is by way of

fitting recognition) that people who had suffered imprisonment under the Fascists would

have gone back to jail or been forced into exile.

For,

wasn't it true that the official hierarchy of the Italian Communist Party itself (PCI) -

though not all of it - was flanked by a clandestine network of people they could trust and

who were stage-managed by the Kremlin.

Nor can

the opposite said to have been proven by Stalin's suggestion to Nenni for moderation when

the latter went to pick up his (Soviet) Peace Prize. Nenni himself rightly informed De

Gasperi (Alcide De Gasperi, Italy's first Christian Democrat post-War premier) and I was

present as under secretary. When Nenni said he was fighting for a policy of neutrality

(Italy's in terms of NATO), Stalin cut him short saying that, because of its geographical

position and history, Italy could not be neutral. What he should do, instead, was fight

extremism within the Treaty. Thus was born Nenni's famed slogan (though it was really

Stalin's) against Atlantic extremism.

In the

consultations at the time of the crisis which beset the government in 1953, Nenni

sustained that the Treaty was not an obstacle to the majority's expansion because

"treaties are just pieces of paper". Later the Socialists and Nenni himself

substantially adjusted this position. And in 1977, even the Communists crossed the floor

in terms of the Treaty so to speak (they had already changed their opinion of European

institutions when Community representative bodies stopped ostracizing them).

Awareness of the need to defend the

nation from the Communist peril rapidly grew, helped along by some providential errors on

the part of the counterparts

|

But

to go back to April 1948, the political climate had been atypical from the last six months

of the year before. On May 31, De Gasperi had formed a government which, for the first

time, included neither Socialists nor Communists who, to great clamor, became the

Opposition. The break had been made necessary by the total divergence on Italy's

international relations.

Meanwhile

at Montecitorio (the Italian lower house of Parliament), Members had pressed on with their

work in a constructive spirit which had never diminished and, at the end of December 1947,

they arrived at the approval of the Constitution with an overwhelming majority.

Also

ratified, though with much more difficulty, was the Peace Treaty which had been signed,

moreover, by the previous coalition government.

In a

relaxed climate, Parliament continued to sit for another month after that December: to

approve the Statutes for Regional Authorities requiring special treatment (Sicily, for

example); to complete the electoral legislation; to draft a first bill on the press

considering as obscene horrific publications and those potentially harmful to adolescents.

I remember that as far as everything else was concerned, legislative functions were

carried out by the Cabinet in which, alongside De Gasperi, Senator Luigi Einaudi lent

prestigious, untiring service yet, by way of an exception, he had stayed on as governor of

the Bank of Italy.

The

election campaign was livening up. The Communist-Socialist merger, borrowing as a model

the Hero of the Two Worlds for the purpose (Giuseppe Garibaldi who unifed Italy in the

mid-19th century), was countered by a group of allied democratic parties who kept their

own identities and who pledged themselves totally to the democratic method (an expression

De Gasperi often used). This term was not rhetorical and, since De Gasperi invited

citizens to vote for one of the government parties, it did not mean that adherence to

Christian Democracy was tepid either.

Awareness

of the need to defend the nation from the Communist peril rapidly grew, helped along by

some providential errors on the part of the counterparts (Communists and Socialists)

themselves. One of these errors was their stipulation of a pact to unsettle Europe. It had

been promoted by Moscow and only came to light in a fortunate press inquiry. Realino

Carboni, editor of the Roman daily Momento Sera, had handed over a copy (of the pact) to

the Prime Minister with fool-proof guarantees of its authenticity.

Luigi

Longo and Eugenio Reale had represented the PCI at the "conclave" held in

Poland. Any suspicion that these two had violated the secrecy had to be dispelled. So I

was sent to Paris to see the French Premier Robert Schuman who saw to (the pact's)

publication which we immediately reproduced and distributed in Italy. The Communists were

quick to issue denials but the specter of this Cominform deeply disturbed the Italian

people. But a few years later after Eugenio Reale had left the Communist Party (officially

expelled from it), he not only confirmed that the pact was authentic but revealed some

disturbing minutes of preparatory meetings. A feature had been Luigi Longo offering strong

guarantees of arms and he even invented stories of mass strikes which never happened. The

PCI was under charge for allowing itself to be put out of government and it had to justify

itself. There was one quirk of fate: the harshest censors (of the PCI) had been the

Yugoslavs who were soon to distance themselves from their great Kremlin comrade encouraged

in this by the Front's defeat (in the Italian elections).

Following the different election

result of 1953 the Prime Minister De Gasperi tried to give us an edifying lesson of life

on that sad evening of July 29, by warning us never to forget that we are all useless

servants

|

A

significant part in the democratic mobilization of 1948 had been played by the religious

organizations. They ingeniously forged ad hoc links with all the forces of Catholic

inspiration in addition to the structures of Catholic Action and other institutions. The

following article is the direct testimony of one of the architects of that Spring

campaign, Cardinal Fiorenzo Angelini, which had been desired and personally supported by

Pius XII.

The

Church is still criticized for its participation in those circumstances in Italy. Appeals

were even made to the (Church-State) Concordat of 1929 - recently introduced to the

Constitution at the time. It was said that its clauses prohibiting priests from joining

political parties (an odd plural for 1929 when there was only one party [Fascism])

sanctioned a sort of vow of political chastity. I remember that, in one of those really

earthy kind of political meetings, I responded to the rebuke of this alleged invasion by

the clergy by saying that, just as farmers were duty-bound to defend their land, the

Church could not stand idly by in the face of the danger of militant atheism. For, it had

already spread its tentacles in acts of violence that the Church had not witnessed for

some considerable time against its pastors and faithful. Call them farmers of souls if you

like, but you can't presume that they will give up without a fight.

The

Civic Committees - as the new strategic Catholic-coordinated formations were called - gave

absolute priority to the fight against abstention from voting (on election day), an

eventuality that was believed would lead to a Front victory. Whether this would have

proven true or not (I think true), people were convinced that the Front would have been

able to ensure that all its supporters would turn out to vote while, in the other camp,

there were sufficiently large areas of alleged electoral indolence, others where voters

could be tempted to vote out of opportunism and others still where voters were afraid.

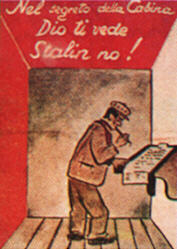

None of the Committees' election posters invited people to vote for the Christian

Democrats. They appealed, rather, against absenteeism at the polls and allowing potential

votes to slip through the net. It must be said, however, that one of their most effective

slogans was the warning that God could see into the polling booth while Stalin could not:

a clear indication as to whom not to vote for.

Analysts

are wary of quantifying the Catholic contribution to the April 18 victory in relation to

the organizational potential of the Christian Democrats and their allied parties. I am not

drawn to such calculations. All I know is that - in addition to the gratitude expressed to

them from outside quarters - a few days after escaping the danger De Gasperi commissioned

me to convey his acknowledgement to both Luigi Gedda and the then Monsignor Angelini. I

also remember that, four years later (though the Civic Committees were not involved), an

unwise and groundless alarm was raised for the outcome of municipal elections in Rome.

This left all us politicians deeply embittered and risked sending us back down the

slippery slope. When he was told of the situation in detail, Pius XII ordered that the

Committee maneuver be deployed again and - though history treated him cruelly - it took

its name this time from the very obedient and holy priest, Luigi Sturzo.

I

did not talk about escaping the danger blithely. The vote cast by Italians was widespread

and explicit. It is a distortion of history to say that it was brought about by external

factors (the American Fleet, a hangover from Yalta, mass financing and such like). It must

be said here that the victory was interpreted in the most linear and right way: it meant

the retention of the coalition - resisting any fundamentalist thrust - and some courageous

development laws (agrarian reform, a special fund for the Italian South, and so on). That

the victory was used to introduce reforms was certainly not popular with voters who, on

that April 18, were seeking to block Communism but not to have resources transferred to

the less affluent sectors. And it was this - among other factors - that led to the

different outcome of the 1953 elections and the ungenerous, forced retirement of the Prime

Minister De Gasperi who, on that sad evening of July 29, tried to give us an edifying

lesson of life by warning us - New Testament in hand - never to forget that we are all

useless servants. |

|